The Rise of the Martian Craze in the Early 20th Century

The early 1900s were a time of immense optimism and technological progress. Innovations such as the automobile, mechanical flight, and wireless communication captivated the public imagination. This era of discovery and possibility was epitomized by Thomas Edison’s belief that “everything, anything is possible” in the next century. Among those who shared this enthusiasm was balloonist Leo Stevens and astronomer David Todd, who, in 1909, set out to prove that communication with Martians was not only possible but imminent.

Their plan involved flying a hot-air balloon 10 miles above Earth so that Todd could send messages to the red planet. The pair was not just optimistic—they were confident. “We will be talking to the people of Mars before the 15th of next September,” Stevens declared. However, their mission never took off due to a lack of funding. Despite their failure, their belief in extraterrestrial communication was fueled by a widespread fascination with Mars during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This fascination was largely driven by Percival Lowell, a wealthy Bostonian who transformed himself into an amateur astronomer after being exiled from polite society for abandoning a marriage proposal. Lowell became obsessed with Mars, convinced that he had discovered artificial canals on its surface—structures that, he claimed, could only have been built by intelligent beings. His theories were based on the work of Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who first observed what he called "canali" (channels) on Mars in 1877. Though Schiaparelli was known for his absent-mindedness, his observations sparked a decades-long debate among astronomers.

Lowell's claims gained traction when Mars passed close to Earth in 1892, making the canals appear more visible. Newspapers like the New York World ran sensational headlines, fueling public excitement. When the Lick Observatory reported seeing lights on Mars, it led to a media frenzy. Were the Martians trying to signal Earth? It was a topic of conversation everywhere.

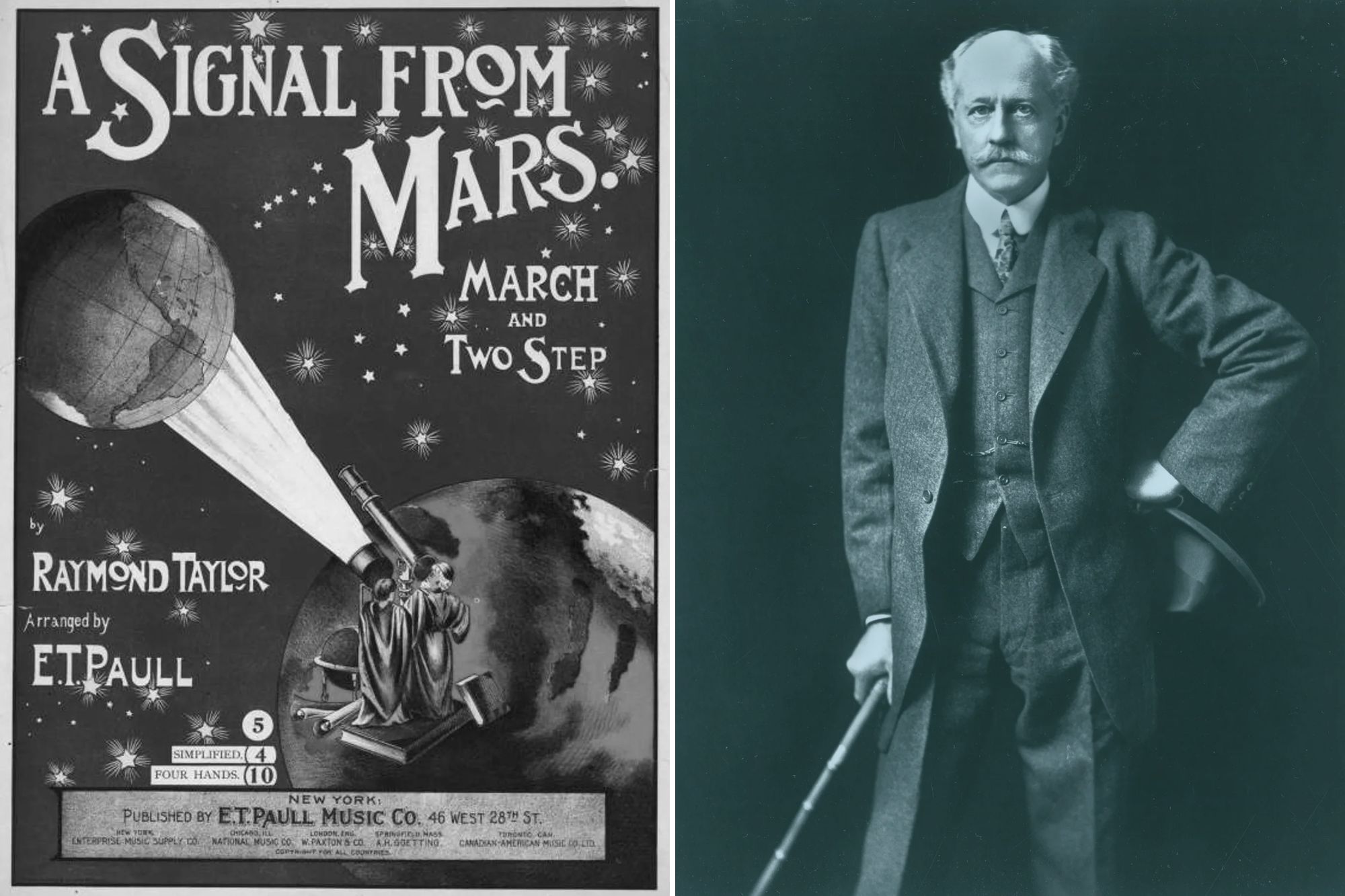

Despite the scientific community's skepticism, Lowell continued to promote his ideas through speaking tours and publications. He argued that the canals were irrigation systems used by Martians to transport water across the planet's arid landscape. His theories captured the public's imagination, leading to a wave of Martian-themed cultural phenomena. H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds (1897) became a bestseller, while dance crazes, Broadway shows, and even advertisements featured Martians.

However, not everyone was convinced. Astronomers like Walter Maunder challenged Lowell’s claims by conducting experiments with schoolchildren, showing that perceptions of Mars' surface varied widely. This suggested that what was seen through telescopes might be influenced by human error or optical illusions rather than actual structures.

Lowell’s reputation suffered further when Eugène Michel Antoniadi, an astronomer from the Meudon Observatory, produced clearer images of Mars that revealed no canals—only natural features. Despite this, Lowell refused to admit he was wrong, continuing to claim new discoveries even as the scientific community labeled him a charlatan.

Though he never proved the existence of life on Mars, Lowell’s work inspired a generation to dream of alien worlds. His legacy, though controversial, played a significant role in shaping humanity’s early fascination with space and the possibility of life beyond Earth.

0 comments:

Ikutan Komentar